Masters and the Media: How Our Perceptions of Augusta Have Evolved

The Masters has always been about more than leaderboards. It’s about the lore, the place, and the feeling that something big is going down on a special parcel of nurseryland in the Peach State.

How we experience that feeling, though, has changed dramatically since Bobby Jones first invited his friends for a low-key spring weekend in Georgia.

Today we can follow nearly every shot, every player, and every swing. But for much of its history, the Masters was one of the most carefully controlled and selectively televised events in sports.

And that restraint shaped how generations of fans came to see and experience Augusta National, and how the story of each tournament was told.

When Masters Week Meant Finding the Right Channel

As the sports world’s official harbinger of spring, the Masters broadcast is appointment viewing. In the 1980s you could find early round coverage on USA Network, a channel we knew better for Cartoon Express, Miami Vice reruns, and pro wrestling. But for one week in April, it would clear the deck and drop us into Augusta for two hours of Thursday and Friday coverage.

Weekend coverage belonged to CBS, the longtime television home of the Masters Tournament. Saturday and Sunday afternoons meant settling in for several hours for familiar hushed voices and that unmistakable Augusta soundtrack.

Before the 1980s, coverage was even more limited. Fewer hours, tighter windows, and a much stronger sense that television was being invited in, not given the run of the place. Back then, people had to rely on the papers to see where their favorite golfers stood. Television may have been capturing the visual experience, but sports reporters owned the story.

“A Unique Tournament, Uniquely Televised”

That phrase came from a 1976 CBS press letter I purchased from an eBay auction featuring memorabilia from the estate of Jimmy Smothers. It included vintage Masters hats, a patron chair with an early version of the Masters logo, two CBS Press Kits from the 1976 and 1977 tournament broadcasts, and decades-old players gifts that I thought might have some resale value. It was a really cool collection, and I paid a handsome sum.

A few years later, upon realizing I may have made a questionable investment, I dug into the pages of the Press Kits looking for anything I could use.

What I found was a time capsule.

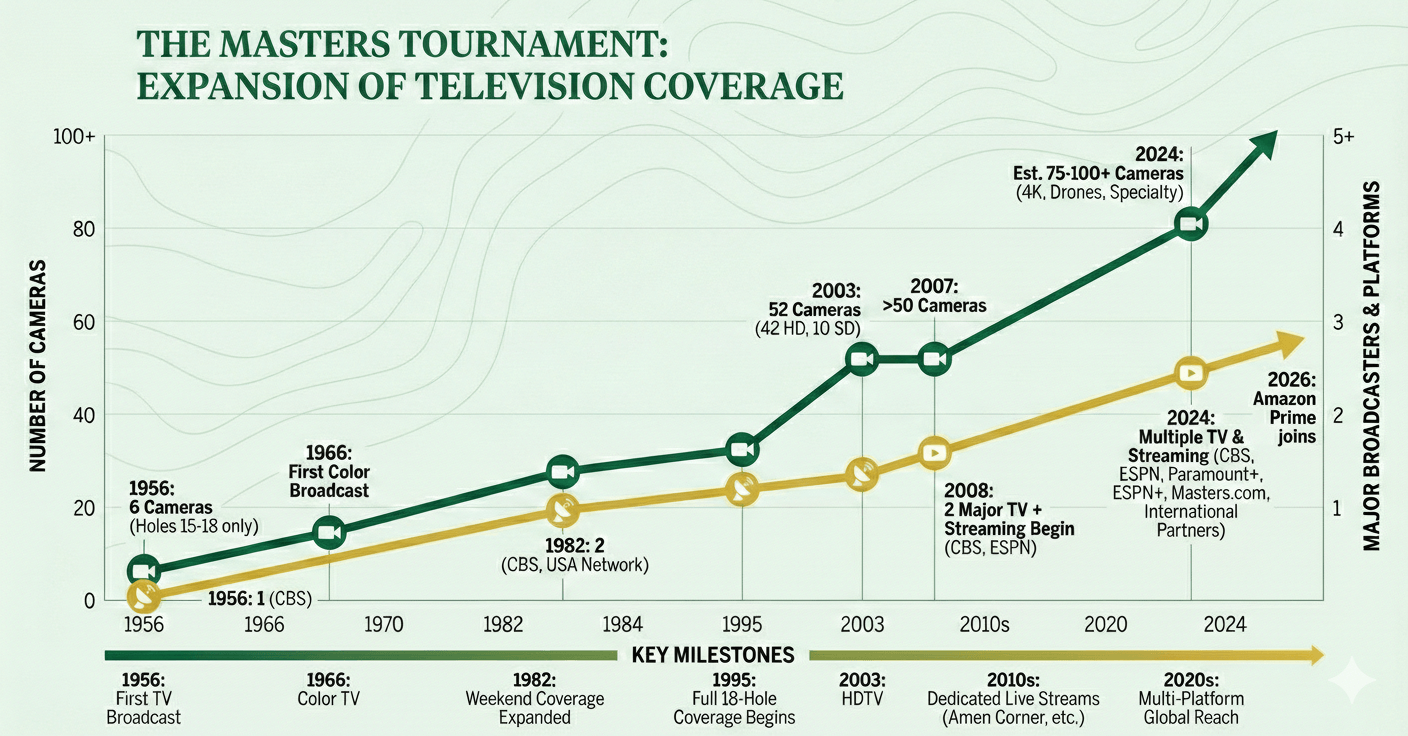

CBS has been the television home for the Masters tournament committee since 1956 and for decades, that relationship operated under conditions unlike any other major sporting event. Under the supreme direction of Cliff Roberts, the Masters exerted considerable influence over their broadcast partner, encouraging CBS to add cameras and even pushing them into the color TV era.

For reporters like Jimmy Smothers, the original recipient of this correspondence, getting a press badge was a privilege that came with serious responsibility. Roberts was known to monitor even the smallest of details under his purview, and without question would have revoked the pass of a reporter who failed to meet his high standards.

It would have been an incredible assignment. Reporters often followed a single player for the opening rounds, recording scores, observations, and moments by hand. Their dispatches would tell the next morning’s story of a tournament most fans had barely seen.

Augusta National and CBS provided press materials designed to support that storytelling, including official Masters scoring sheets with space for detailed notes. Journalists would not be supplementing television coverage, in fact it was the other way around. They were the primary channel through which fans experienced the Masters.

Back When You Couldn’t Just Watch the Masters

In the early 1970s, television coverage of the Masters was extremely limited.

For the first two rounds, Augusta National released only about ten minutes of taped highlights. That was the visual record of Thursday and Friday. The rest of the tournament lived in radio reports, patron memories, and the written accounts of the press corps.

Weekend coverage existed, but even that was constrained with 23 CBS cameras across only the final 7 holes. That might sound like a lot, but viewers typically saw two hours on Saturday and two hours on Sunday.

To put that in perspective, CBS broadcast exactly four hours and ten minutes of live Masters coverage in 1976. Across a tournament that unfolded over more than forty hours of actual play, television showed roughly ten percent of the action.

That scarcity gave the Masters an aura unlike any other sporting event. Fans did not consume it continuously. They experienced it in fragments, and those fragments carried enormous weight. You either had to have a ticket (which got easier once the Masters ticket lottery opened in 1995), or you took what you could get.

1976–1977: A Turning Point on Television

CBS’s relationship with the Masters dates back to 1956, and the technical setup of those early broadcasts reveals just how limited television once was. Kids today just don’t understand.

The first telecast used seven cameras, focused almost entirely on the closing stretch: the 15th, 16th, and 17th greens, the 18th fairway, and the 18th green. On Sunday, they added two more cameras on the 15th and 17th fairways and even placed one inside the clubhouse suite of Clifford Roberts.

By the mid-1970s, things began to change.

CBS, fresh off a 1975 Emmy for that year’s Masters broadcast, started expanding the scope of coverage. Extra cameras were added in 1976 to provide more on-course visuals. Then in 1977, television coverage grew again, both in depth and in reach.

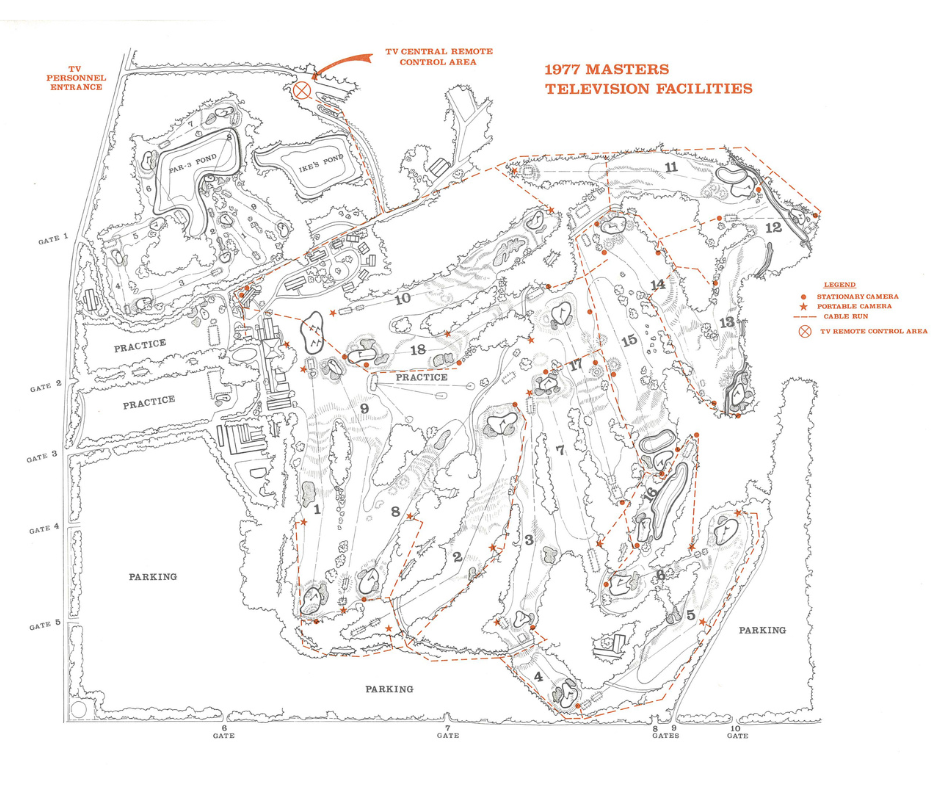

1977 Masters Television Facilities, Courtesy of CBS

Weekend telecasts typically ran from 4 to 6 p.m. Eastern and were carried live not only in the United States and Canada, but also in Tokyo. The Tokyo Broadcasting Company delivered a live telecast via satellite for the second consecutive year, a significant technological feat at the time.

Sponsors like Cadillac, General Motors, and Travelers Insurance Companies supported the growing broadcast infrastructure. Travelers even produced a motion picture about the tournament, recognizing the Masters’ increasing importance as a visual medium.

The footprint of the broadcast was expanding, but it was still carefully managed.

The Wizard in the Corner: Clifford Roberts

Much of that management came down to one man: Clifford Roberts.

As co-founder and chairman of Augusta National Golf Club, Roberts understood television’s importance to the Masters. And like everything in his life, he obsessed over it.

Roberts personally reviewed broadcasts and provided feedback to CBS. Praise, when earned, was delivered directly. So was criticism, which he delivered in an unmistakably convivial manner. According to David Owen’s book, The Making of the Masters, serving on the Masters broadcast “served as a sort of advanced-degree program for sports broadcasters.”

One such broadcaster, Jack Whitaker, got a tough schooling after he referred to a Masters crowd as “the mob, running after [Arnold] Palmer,” which Roberts felt was both inaccurate and disrespectful to his patrons. At his direction, Whitaker was summarily booted from the broadcast and replaced by Pat Summerall (though he would be allowed back in 1972).

Roberts approached television coverage with the same precision he applied to every aspect of the tournament. Nothing about the Masters was accidental, and television was no exception. Roberts stepped down as chairman in 1976, marking the end of an era, but the broadcast structure he helped shape defines the Masters to this day.

The Men Who Brought It to Life

Early Masters broadcasts relied heavily on the voices describing the action.

There were elevated broadcast towers scattered across the property, and commentators worked from the ground, assigned to specific holes, reporting from within the landscape itself. Among the 1976 cast were Vin Scully, longtime voice of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Pat Summerall of NFL fame, and the repentant Jack Whitaker.

Their job was not simply to describe shots. It was to translate a tournament viewers could only partially see. And fittingly, Roberts had his hands on that too, working with CBS to explore new ways to cover the action such as placing a camera behind a golfer to capture his ball flight.

The iconic voices of sport have always been associated with the Masters, and our pleasure continues in the modern era with Jim Nantz, who first hosted CBS’s Masters coverage in 1989. Over more than three decades, his voice became inseparable from the tournament itself.

His delivery, reverential and welcoming, helped turn the Masters into something more than a broadcast. It became a ritual. But enjoy him while you can, because he has decided to call his last Masters in 2036.

Streaming Changed Everything, And Augusta Leaned In

Through the 1990s and early 2000s, Masters coverage expanded significantly with more early round action and lengthened weekend windows. Fans could now follow more of the field and see more of the course than ever before.

By the early 2000s, advances in digital production and satellite distribution laid the groundwork for featured group coverage and the first online streaming offerings. As the world entered the digital age, the Masters Tournament Committee was already well adapted to the times.

In 2026, you will be able to watch 75-85% of meaningful tournament action and 100% of impactful shots through live or near-live video. A big part of this is credited to Augusta National’s full-throated embrace of streaming.

Instead of handing its digital future entirely to outside platforms, the club built its own ecosystem. The Masters app and website quickly became one of the most sophisticated event experiences in sports.

Featured groups. Dedicated Amen Corner feeds. Individual player tracking. On-demand highlights. Customizable leaderboards. For golf fans, it is hard to argue there is a better event app in sports. You can follow a single player, a single hole, or the entire field, all from the same place, and all for free.

How All This Changed Our Perception

In the early days, Augusta felt more opaque; viewers saw a few hours of coverage and filled in the rest with imagination, accounts from lucky patrons, and the next day’s newspaper.

Today, the course is familiar in a way it never was before. We know the slopes, the sightlines, the angles. The players are more accessible. The tournament is more present in our daily lives.

But the core feeling remains the same.

The same exclusive fairways. The same back-nine tension. The same Sunday walks up 18.

The difference is that now, instead of waiting all afternoon for a glimpse or your favorite reporter’s story, we carry Augusta in our pocket, wear the iconic Masters logo on our clothes, and revisit those moments whenever we like.

What a world, and what a time to be alive.