The Aquatic Blueprint Beneath Augusta National

What Augusta National Teaches Us About the Way Water Shapes the Land

Every April, millions of people study Augusta National Golf Club without realizing they are also watching a masterclass in hydrology.

Viewers talk about pin positions, swirling winds, and lightning-fast greens. Players talk about nerves and strategy. But underneath all of it is something quieter and just as powerful: the way water moves through the land.

Augusta is famous for its beauty. It should also be famous for its drainage.

Before It Was Augusta National

Long before it was a golf course, the property was known as Fruitland Nursery, a sprawling plant nursery filled with trees, shrubs, and flowering plants from around the world.

When Bobby Jones first visited the land in the early 1930s, he did not see fairways and greens laid out with bulldozers. He saw natural corridors, gentle slopes, and open spaces that already felt like golf holes. The land presented a course to him. Designers later refined it, but the framework was already there.

That framework was shaped by water.

The same ridges, low ground, and natural drainage paths that once helped manage irrigation and plant growth at the nursery were part of what made the property so compelling for a golf course. The terrain already had flow. Jones and Alister MacKenzie worked with that flow rather than fighting it.

The Course You See Is Built on the Water You Don’t

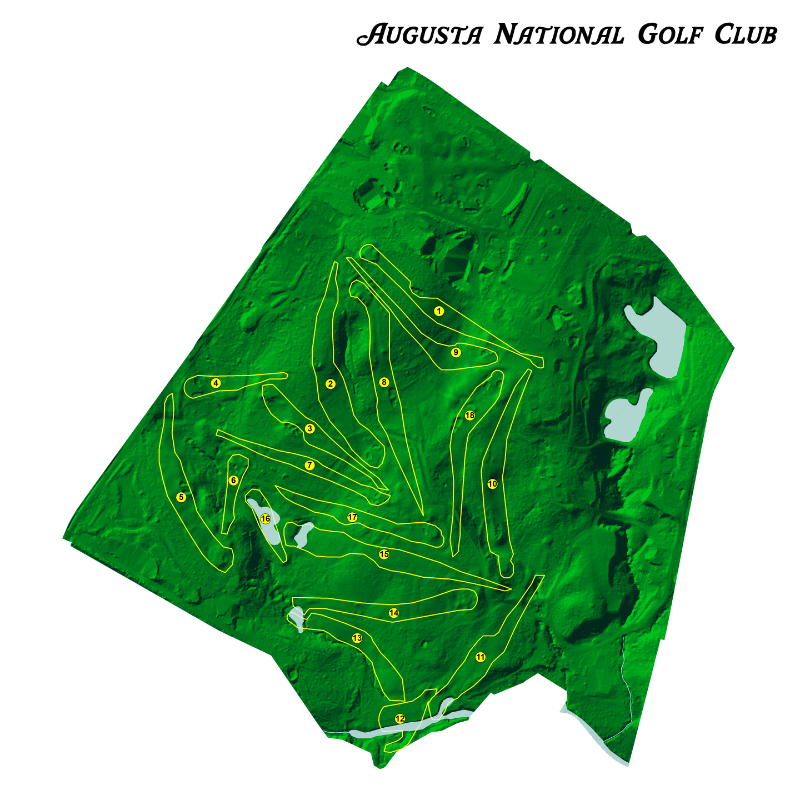

Rae’s Creek gets the attention because it frames Amen Corner and shows up on every highlight reel. But it is just one visible piece of a much larger water story.

The entire property is shaped by subtle ridges, low corridors, and natural channels that guide rainfall across the landscape. High points shed water. Slopes funnel it. Low areas collect and slow it down. Some of that movement is visible in creeks and ponds. Most of it happens quietly across turf and soil.

An aerial layout featuring the hydrology of Augusta National Golf Club.

It is a reminder that every landscape, not just famous golf courses, is designed first by water.

Elevation Is a Water Story

If you have ever walked Augusta, you know it is anything but flat. Those elevation changes are not just dramatic for golf. They are how the land drains.

Water always moves downhill, and over time it carves patterns into the terrain. Valleys form where water consistently flows. Ridges stand higher because water runs off them. The shape of the land is a long record of where water has been and where it still wants to go.

This is true at Augusta. It is also true in your state, your favorite national park, and the places you hike, fish, and explore.

Creeks, Rivers, and the Hidden Networks Between Them

Rae’s Creek is part of a branching system, with smaller upstream channels feeding into larger ones. Hydrologists call this a stream network, and it exists everywhere, from mountain headwaters to coastal plains.

Some streams are obvious. Others only carry water during heavy rain. Many are buried in woods, fields, or neighborhoods, quietly connecting one part of the landscape to another. Together, they form the circulatory system of the land.

When you start seeing these networks, you realize that maps are not just lines on paper. They are stories about how water ties a place together.

Why Hydrology Maps Change the Way You See a Place

A hydrology map does something simple and powerful: it reveals the structure of water across a landscape.

Suddenly, ridgelines make more sense. Valleys feel more intentional. You can see why certain towns sit where they do, why trails follow certain routes, or why a lake exists in one basin and not another. You start to understand how rainfall turns into creeks, how creeks join rivers, and how entire regions are connected by drainage patterns.

It is the same idea Bobby Jones responded to at Fruitland Nursery. The land already had order. Water had already done the design work. He just recognized it.

From a Nursery to a National Landscape

Augusta National is a relatively small property, but its origin story reveals a universal truth: water is the quiet architect of the places we love.

What Bobby Jones saw at Fruitland Nursery is what hydrologists and mapmakers see at a much larger scale. Entire states, watersheds, and national parks are organized by the same forces that shaped those famous fairways and valleys.

The forests, the fields, the cities, the courses we play, and the trails we hike all sit on top of these water-driven patterns. Once you see them, you cannot unsee them.

That is the idea behind detailed hydrology maps. They are not just decorative. They are a way to appreciate the hidden structure of a place — the creeks, watersheds, and drainage networks that define its character long before roads and buildings arrived.

The next time you watch a shot fly over Rae’s Creek, remember: you are not just looking at a golf hole. You are looking at the same forces that shaped entire regions.

Water did the first draft. We are just living on top of it.